Liner Notes

(1) A concept album is a studio album where all musical and lyrical ideas contribute to a single overall theme. It is often accompanied by a set of liner notes that comprise a variety of texts including fact, anecdote, image or photograph, critical essay or comment, biography, credits, acknowledgements, details on each musical piece or artistic work, and a social or historical context to the album and its contents, or a combination of some or all of these.

(2) The Liner Notes for my concept album are just such a reflective combination arranged across a timeline of historical events and artistic projects that were made in response and in reaction to those events, and that are referenced in Wall of Noise, Web of Silence, a creation which synthesises the competing and significant aspects of my practice in terms of content, methodology, sensibility, scale and motivation.

(3) The Timeline of the Liner Notes spans 20 years from 1997 – 2016. It is bookended by the rise of the One Nation Party and its second political coming at the 2016 Federal Election. In between are the Hearing of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights into the Stolen Generations (2000), the Tampa Affair (2001), the Abu Ghraib prisoner and torture scandal (2003) and the trajectory of governments led by John Howard (1996-2007), Kevin Rudd and Julia Gillard (2007-13,) Tony Abbott and Malcolm Turnbull (2013-) and the election of Donald Trump as American President in 2016.

(4) If one imagines the two sides of the concept album as thesis and anti-thesis, the Liner Notes are the base on which the two parts pivot as they turn towards and away from each other. There is vertical integration of the Liner Notes into the dialectic that is characterised by points of intersection with specific tracks from Side 1 Wall of Noise, specific elements of Side 2 Web of Silence and the artist’s back catalogue. This process seeks to reflect upon the ideas and propositions of the concept album, and how these create, correlate and collude with my practice.

(5) The majority of the artworks referenced here were created and produced within the company frame of not yet it’s difficult (NYID) through grants, commissions and awards from local, national and international agencies and presented by venues, arts centres, festivals, in Australia, Europe and Asia including the Sydney, Brisbane, Adelaide and Melbourne Festivals, Vienna Festwochen, Aarhus Festival, Cankarjev Dom, Expo 2000, Dublin Fringe Festival, Hellerau, the Seoul Performing Arts Festival, the Seoul International Dance Festival and Liverpool Capital of Culture. NYID was founded in 1995 by David Pledger, Peter Eckersall and Paul Jackson and is regarded as one of Australia’s seminal interdisciplinary arts companies. This core artistic practice is augmented by my work as an artist, activist, advocate and curator with local, national and international governments, arts agencies, cultural institutions, artists’ collectives, individual artists, and the philanthropic change-agent, Igniting Change.

the austral/asian post-cartoon: sports edition, 1997

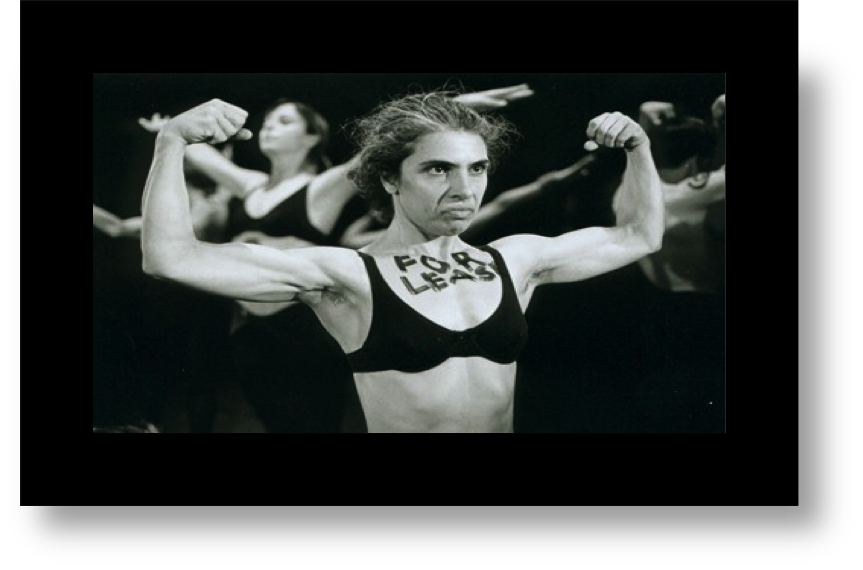

(1) One Nation 1997 On the opening night of NYID’s The Austral/Asian Post-Cartoon: Sports Edition, more commonly referred to as The Sport Show (1997), I was advised by a concerned journalist to remain in the theatre as disgruntled members of the audience intent on inflicting physical harm to my person were waiting outside The Malthouse Theatre.

The reason for their disquiet was a scene in the performance called The Coach’s Speech – which concludes Side 1 Wall of Noise – in which a Vietnamese performer was savagely beaten for his ‘not belonging’ to Australia’s National Team. Its agency as a political intervention was rooted in its crossing the line from presentation – which had characterised the performance to that point – to representation. The journey of this crossing was slow and deliberate to repercuss deeply within the psyche of the audience. Despite the fact the actor was wearing protective sports clothing, despite the fact that we were in the heightened aesthetic space of a theatrical production and despite the fact the audience were taken on the journey with humorous intent, the first 30 seconds after the beating, in which the perpetrators and the audience witnessed a human being lying prostrate, were the longest 30 seconds of my working life as an artist. I never knew whether the audience was going to go crazy, walk out or initiate some independent action. On one occasion an audience member plaintively asked: “Won’t someone help that poor man?” No one did.

It all works out well in the performance. After about a minute, the actor Kha Tran Viet jumps to his feet and proceeds to instruct his perpetrators (fellow actors) on the deficits in their fighting skills in the context of Vovinam martial arts of which he is a teacher. It was a way of bringing the audience back into the performance proper and re-connecting them with a safer, discursive space.

However, this scene deeply affected many audience members because it disabled their agency, a condition which echoed their daily life experience as citizens within Australian society. The scene was inspired by Kha’s own experience running away from skinheads in Melbourne’s CBD at the height of Pauline Hanson’s first iteration of One Nation [130] and it viscerally reminded the audience of their complicity in Australia’s racism by maintaining their silence and inaction. Hence the re-action.

Of interest is the corporeality of this scene of violence against another. Prior to the scene, the actors’ bodies were upright, muscular and available, athletic in their poise and comportment. This state slowly deteriorated into the animalistic as a pack mentality overwhelmed the perpetrators – backs bent, saliva and sweat running, arms and legs akimbo as the contagion of violence spread like a virus. This is in stark contrast to the ‘victim’ whose body can only absorb the punishment as it slowly bows, back arched, hands across the face, bent to one knee then both, finally collapsing slowly to one side as exhaustion overwhelms the survival instinct: defeated.

In the arc between these two physical positions – the upright and the prostrate – lies the dynamic between the embodied citizen of a democracy and the embodied citizen of a neo-liberal state, a dynamic that was consequnetial to John Howard’s Prime Ministership and that, using the body as a map, I charted through the performances WS:HDQ (1996) which pre-dated The Sport Show, Scenes of The Beginning from The End (2001), Journey To Con-fusion #3 (2002), K (2002), Blowback (2004), apoliticaldance (2006), The Dispossessed (2008) and Strangeland (2009).

It is the body that manifests our fears, our neuroses, our true sensibility. It is the body that shows us what we are when our mind deceives us. [131]

strangeland, 2009

This downward, dorsal trajectory of the citizen began with Howard’s infantilization of Australian society, and manifested in the pathologically childish behaviour of Labor’s subsequent turn in office (2007-2013) which, in turn, was punctuated by Tony Abbott’s 28-second punch-drunk tantrum recorded mid-interview with a TV-journalist in 2011 and book-ended by his pugnacious, prime-ministerial threat to ‘shirtfront’ the visiting Russian head-of-state, Vladimir Putin in 2014.[132] This abject behaviour of Australia’s mainstream-party political leadership created an institutionalised ambience of permissiveness with regard to the body in Australian society that accommodated the physical abuse and state-sanctioned torture of those seeking asylum in the gulag of Australia’s detention centres. The more subtle, on-shore and related modes of this permissiveness lie in institutional coercion and attrition, and are umbilically connected in managerialism, the most toxic of which is practised by the Department of Immigration and Border Protection which I reference in Side 1’s 45rpmanagerialism in society.

From The Sport Show (1997) to Strangeland (2009), I expressed in corporeal terms what began as an undertow in Australian society with One Nation and which ended up as a wave of physical deprivation. Side 1’s 45rpmanagerialism in democracy Notes 23-52 outlines the extreme consequences of this wave on an actual body. I feel that this body, that of the self-immolated asylum-seeker, operates not just as a metaphor for the deprivation of Australia’s policy positions but as a symbol of the condition of our morality. It was a symbol I repeatedly offered up in my artistic practice as a warning then a judgment.

In 1997, Pauline Hanson founded the One Nation Party, a political party with a conservative and populist platform.

Director’s note: http://www.notyet.com.au/project/apoliticaldance

(2) Stolen Generations, 2000 In 1996, ‘Little Johnny Howard’ – the erstwhile butt of a generation of jokes within his own party – stripped Paul Keating of the prime ministerial mantle and plotted an 11-year durational performance of resentment. Pauline Hanson was Howard’s fillip in the early years and he masterfully exploited her presence using her anti-Asian, anti-Indigenous views to run interference for his mainstream version that had significant traction in marginal electorates.

Despite this, by 2000, Howard was considered a ‘bit on the nose’ with his awkward, parochial and unworldly lead-in performances to the Sydney Olympics completely at odds with Keating’s lingering legacy of a progressive and liberal Australia. But Howard weathered the unpopularity and his influence amplified, creating an atmosphere of censorship that portended the curtailment of freedom-of-expression, more commonplace today.

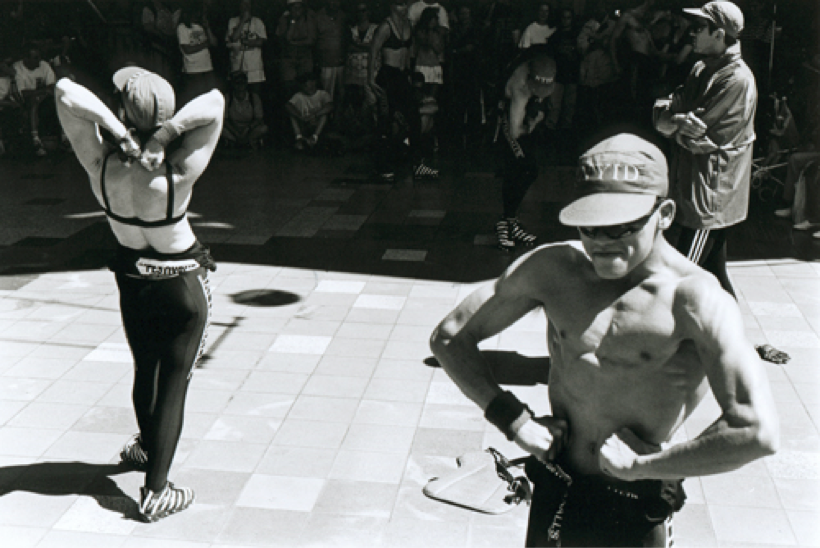

In my own case I was presenting Olympic Training Squad in Hannover, Germany, at the Australian Pavilion for EXPO, a program under the remit of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

A precursor to The Sports Show, Training Squad had its genesis in 1996 as a response to the Victorian Liberal Government’s appropriation of public space for urban development. A cube of 9 performers ran at pace through the streets of Melbourne’s CBD stopping to occupy the City Square, Bourke Street Mall and Southbank with a gestural and spoken vocabulary drawn from sports actions and spectatorship.

In Hannover, the performance was expanded to include topical references to the Olympics which coincided with the July 2000 Hearing of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights, the Stolen Generations, matters from which blew up in the face of John Howard’s government. The UN’s Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination took the Government to task for its failure to support a national apology and its inadequate financial recompense for the suffering inflicted on indigenous people separated from their families.[133]

In the weeks before the Sydney Games, indigenous athlete Cathy Freeman had been critical of Prime Minister Howard for refusing to apologise for the past in the context of the ‘stolen generations’ debate.[134]

training squad, 1996-2013

In support of Freeman’s position, we invited the European audience to use our bodies as a canvas to sign a petition to the Australian Government. Standing in front of the Australian Pavilion, stripped to the waist, we offered textas to the thousand audience members we drew to each performance inviting them to write a message to John Howard and his government in support of Cathy Freeman’s stand. After a few of these signings I was engaged backstage by a senior DFAT bureaucrat and strenuously advised to delete the scene from the performance – a directive I refused to obey. Within a day, our on-site European agent had been contacted by a second DFAT bureaucrat drawing their attention to the political nature of the performance. In order to get some artistic breathing space for ourselves, we resolved to publicise DFAT’s intervention in the Australian media. Reporting accusation-and-denial can sometimes do wonders for calling off the police.[135] We were not bothered again and the performance proceeded with the body-petitions.

Nevertheless, it presaged a growing dis-ease within the Australian bodypolitic that metastasized into the cancerous culture wars of Howard’s later years, the legacy of which is evident in the Turnbull Government’s adversarial engagement with the arts, in particular, its desire to bring the Australia Council closer to it in order that it might reduce its independence and funding efficacy, and make it an arm of the government rather than an arm’s length agency. This is the ambient discourse of Side 1’s mini EP (not the style council). It resonates a warning I received from an audience member on the opening night of Blowback (2004) to “watch out, mate.” Two years later, when asked by an Australian presenter if I was concerned for myself, if not my practice, I have a clear memory of hesitating before responding. An atmosphere of censorship and self-censorship prevailed in Howard’s final years and its institutionalisation is his legacy.

Concluding Observations by the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination : Australia. 19 April 2000. CERD/C/304/Add.101. (Concluding Observations/Comments) para 13. at UNHCHR.ch

The Australian 20/9/2000 https://www.mailarchive.com/recoznet2@paradigm4.com.au/msg04315.html

(3) Tampa, 2001 In August 2001, the Norwegian freighter, MV Tampa, carrying 438 refugees rescued from a cap-sized boat in international waters sought permission to enter Australian waters, a request John Howard’s Australian Government denied. The Tampa Affair precipitated a generation of attrition by Australian governments against those seeking asylum via boat that persists to this day. The complicity of the Australian people in this persecution is one of the most divisive issues in contemporary Australian society. Once perceived as a compassionate and welcoming country, Australia is vilified internationally for its (mis)treatment and incarceration of the world’s most vulnerable people. As an artist who has worked internationally since 1990 the constant and increasing volume of inquiry from foreigners as to the motivations behind our stance has become ever more embarrassing as our failure as a civil society has been exposed.

To house the asylum-seekers, a gulag of detention centres was created across Australia that include(d) Villawood (NSW), Maribyrnong (Vic), Baxter (SA), Woomera (SA), Curtin (WA), Perth (WA), Scherger (QLD), Yongah Hill (WA), Wickham Point (NT), and offshore facilities at Christmas Island, Manus Island and Nauru. Reports of physical and sexual abuse, mental health problems, torture, rape, child abuse, murder and self-harm have been in the public domain since early in the gulag’s establishment. In response, many Australians organised support and advocacy groups to provide legal advice, visits, moral encouragement and government lobbying. This has been done by individual citizens and organisations such as the Melbourne-based Asylum Seeker Resource Centre (ASRC). Many more Australians were wilfully wedged by the two major political parties which continues to drive electoral collateral for them both.

Three of the more outstanding acts of resistance were made in the artspace by the one artist. For Close the Concentration Camps (2002), performance artist Mike Parr sewed his lips and face with thread echoing the acts of protest of the Woomera asylum seekers only months earlier. For ‘a stitch in time’ (2003) he invited online spectators to deliver electric shocks to his body by clicking their computer mouse as an act of ‘democratic torture’ after he stitched his face into a caricature of shame.[136] In 2005, for Kingdom Come and/or Punch Holes in the Body Politic Parr, dressed in an orange uniform evoking those of the inmates of Guantanamo Bay, ‘sat in a gallery connected to a low-voltage electroshock system that was triggered by audience movement…(his) spasm and facial expressions were digitally captured, manipulated, and immediately projected onto the wall of an adjacent room.’[137] In these works, the artist violates himself and is violated by an other. Through interactivity and mediation, his body becomes the shared space for both actions. It was the creation of this shared space that attracted me and paralleled my own timeline as an artist.

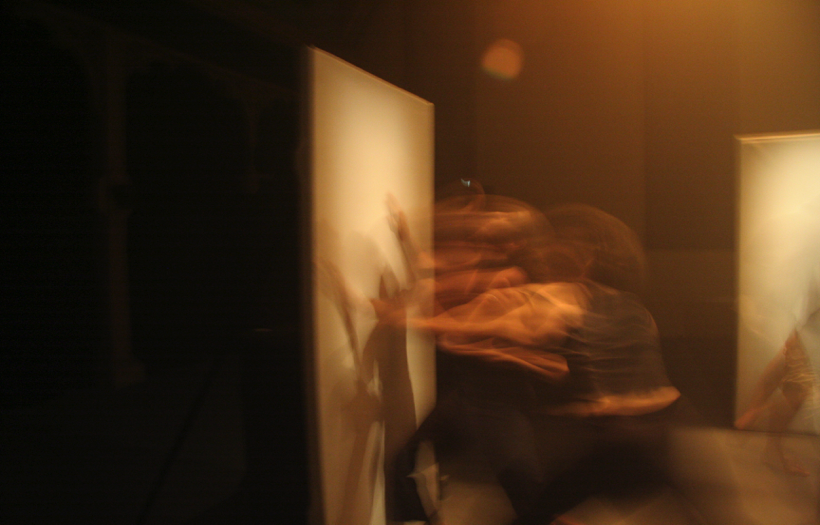

Until The Sports Show, my approach to the body had been to concentrate on acts of violence against another. This trope was expanded to a variation of the same in Scenes of The Beginning From The End (2001) which directed violence against a randomly selected audience member and in K (2002-5) where the violence was delivered remotely by the state against a detained citizen. My response to the establishment of the detention centre gulag was to create a new dramaturgical trope – violence against oneself – that would accompany, amplify and inextricably link with violence against another. It manifest most purely around a scene I created for Journey to Confusion #3 (2002) and re-purposed for apoliticaldance (2006), and which was re-framed and customised for the narrative and ambient needs of Blowback (2004), The Dispossessed (2008) and strangeland (2009).

Violence against oneself begins with a ‘character’ or performer throwing themselves repeatedly at a wall. Over 7 years this strategy was employed with various motivations – torture, frustration, despair, shock, incomprehension.

apoliticaldance, 2006

In Journey To Confusion and apoliticaldance, the motivations were primarily self-harm. The format was roughly the same in both performances. Three or more couples walk arm-in-arm to and from their home, represented as a specially constructed white rectangular, upright wall. They take it in turn to throw each other forcefully at the wall, picking up their fallen partner and throwing them against the wall until they can no longer get up. If one is defeated before the other then the remaining person runs time and again into the wall, smashing themselves until they too can no longer move. All the while, ‘A World Of Our Own”, by Australian 1960s pop group The Seekers, is played at volume. These lyrics open Side 2 Web of Silence but are worth repeating here in full:

Close the doors, light the lights.

We’re stayin’ home tonight,

Far away from the bustle and the bright city lights.

Let them all fade away.

Just leave us alone.

And we’ll live in a world of our own.

We’ll build a world of our own

That no one else can share.All our sorrows we’ll leave far behind us there.

And I know you will find

There’ll be peace of mind

When we live in a world of our own.

This scene is emblematic of two sides of a mirror: on the one side detainees causing self-harm and on the other ordinary Australians, for whom complicity in the self-harm is unbearable. In Blowback, the motivation of self-harm gives way to deep frustration which manifests like a tic in the soap-opera character, Scott, who randomly flings himself into the white walls. In the later works The Dispossessed and Strangeland, there are no motivations for this violence; running into walls simply becomes a habit, a form of expression by human beings who cannot remember its origins and whose humanity has been reduced by the attrition of the system in which they live, the aesthetics of which were informed by the actions of the bodies in Samuel Beckett’s dystopian novella, The Lost Ones. The normalisation of this action toxifies, corrodes and ‘punches holes’ in the bodypolitic, damaging those whose habit it is and desensitising those who bear witness.

The Infinity Machine: Mike Parr’s Performance Art, 1971–2005 (review) by Christine Stoddart in TDR: The Drama Review, Volume 55, Number 3, Fall 2011, pp 189-191

(4) Abu Graib, 2003

Director David Pledger’s physical explorations may be thought of as an “acoustics of the body”. Just as sounds bounce off hard surfaces or are deflected by softer ones, causing noises to inhabit each space in a characteristic way, so the sensorium of the body is affected by the materials about it.[139]

The materials about the body that critic Jonathan Marshall refers to here are social. They reverberate, creating a sonic aura which is invisible and indivisible with other elements in the sensorium. Depending on those elements the affect can be pleasant or unpleasant. In the aesthetic environment of my multi-media theatre production K, the primary material is the Foundation Sound which begins as a tone amplified by frequency, intensifies with volume and pushes hard against the walls of a transformed Touring Hall in Melbourne Museum until its oppression is altogether complete and surprising for the audience as they are immersed in a system of representation that compels them to consider their complicity in the Iraq War where the children’s song, I Love You, by Barney the Purple Dinosaur, was played on a 24-hour loop to captured Iraqi soldiers in torture-containers in American military facilities. The Foundation Sound is similarly employed to under-score Side 1 Wall of Noise, to draw the audience, the reader, into the aesthetic dimension of my scholarship.

The use of sound as torture was widespread during the Iraq War, in particular the technique of playing American pop and rock, repeatedly, and at volume. At Abu Graib, Haj Ali, the hooded man in the infamous prison photographs, was stripped, handcuffed and forced to listen to American singer-songwriter David Gray’s Babylon, ‘at a volume so high he feared that his head would burst’.[141]

In Blowback (2004), Darko, a resistance fighter planning an online cultural action against the occupying American forces in a fictional Australia, inverts this torture strategy by singing KC and The Sunshine Band’s Give It Up to block the painful, shock-therapy-like treatment his female torturer employs to invade his mind. Sound can be an offensive and defensive tool.

Blowback, 2004

Violence is integral to the prosecution of any war. Until the Iraq War, however, the use of torture was considered to transgress the ‘rules of engagement’ despite its routine use in whichever theatre it made an appearance. All that changed when the American government legislated the Military Commissions Act of 2006. Amnesty International determined the Act

Permit(s), in violation of international law, the use of evidence extracted under cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, or as a result of “outrages upon personal dignity, particularly humiliating or degrading treatment”, as defined under international law. [142]

When a society legislates the acceptance and normalisation of torture, it steps away from universal human rights towards barbarity. Australia’s proximity to America in the Coalition of The Willing meant it to, by proxy, politically and civically condoned the torture of prisoners-of-war. At this moment, the ambience of permissiveness in regard to the body that marked John Howard’s prime ministership concretizes into a politico-legal structure that atomises the body of the citizen – in the first instance the citizen of the other, the foreign citizen, and ultimately the citizen that is us. Our bodypolitic is re-configured around this newly negotiated citizen’s body and our values shape-shift around the idea of whose body can now be tortured – the soldier, the asylum-seeker, the refugee, the other, the us.

That the lines of civilization are now blurred is in large part a consequence of the alchemy of neo-liberalism and managerialism. One of Elton Mayo’s motivations for developing Managerialism, was his scepticism of the individual and the community to create social change. He believed this capacity was innate to the organisation. In the social context of the neo-liberal project, the ‘individual’ and ‘community’ are subsumed into ‘the organisation’. This elision breeds certain human behaviours – aversion to risk, susceptibility to fear, a competitive default setting.

In his novel, Super Cannes (2000) – a seminal reference for my performative explorations – JG Ballard unpacks the disease that festers beneath a gated community of individuals employed by an unspecified organisation.[143] The symptoms of the disease are insomnia and stress. As a cure, the community’s psychiatrist encourages aberrant sexual and physical behaviour so the residents might relate to people and things other than their jobs which tie their souls to the rules and etiquette of an oppressive and detrimental extreme. This notion of ‘otherness’ is central to the thesis of managerialism as it feeds on exclusion, isolation and exception. In the community sense, it means building a wall around homes, sealing and isolating our domestic world, ‘a world of our own that no-one else can share’.[144]

Managerialism brings its own distinct accent to the pathology of an organisation and ultimately to a society. It demands caution when risk is necessary; it commands the protocols of competition when justice and compromise could be employed as humane options; it displaces common sense with institutionalised rule. When a bureaucrat in George W Bush’s administration decides that a higher quality of information needs to be solicited from prisoners-of-war, the directive oozes down the chains of power to the grunts on the ground and they implement a horror that transgresses civilised rules of engagement. The greater horror is made when the transgression is legislated by the managerialist politicians as permissible not just to mitigate the blowback but to inflict more physical pain, now state-sanctioned.

In my work, the vertical integration of managerialism is epitomised in K (2002-5), a conflation of Franz Kafka’s The Trial, George Orwell’s 1984 and Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451. A world is described in which an automated system of torture is activated against a citizen randomly drafted by a mobile-surveillance dragnet. His crime is the possession of a book, Kafka’s The Trial, for which he suffers a fatal interrogation by a militarised bureaucrat. K exposes the concentric circles of complicity in which managerialism and neo-liberalism operate. They occur not just in the life-and-death context of war but in the more prosaic and no less influential parts of our social sectors including education, the arts and culture. They are circles created by the actions of violence against an other, against oneself and, once institutionalised, constitutes a violence against society.

Blowback, 2004

One of the most egregious examples of this is the covert national surveillance system installed by the US Government post-9/11 which was exposed in 2013 by whistle-blower, Edward Snowden. This state-sanctioned breach of privacy constituted an unheralded attack on its own by a democratically-elected government. In the future narrative of modern democracy, it is a scene that may signal the beginning of the end.

Jonathan Marshall. Territories of Sound. Umelec, Vol. 5-6, 2001

Amnesty International. Turning Bad Policy into Bad Law. USA Military Commissions Act of 2006. September 28 2006.

JG Ballard. Super Cannes. USA. Picador 2000

The Seekers, A World Of Our Own. By Tom Springfield. Warner/Chappell Music. 1965

(5) Re-Calibration The triumph of Kevin Rudd over John Howard at the 2007 Election is an historical marker in terms of Australian politics, Australian society – and my work as an artist. Whilst I had enjoyed artistic success, the changes in society I had hoped my work would accompany, did not in fact materialise. My final artistic offer of this period was apoliticaldance which preceded Howard’s defeat by a year. It was framed by the question: what does the body look like after 10 years of neo-conservative rule?[145] It was a question that persisted throughout The Dispossessed (2008) and strangeland (2009) and which seeps through Side 1, Wall of Noise.

In truth, I had begun to question deeply my role as an artist. I was very conscious that I had adopted the position of the antagonist, seeking to critique, to call out inconsistency and deception, to shout loudly when injustice was present and warn conspicuously when I had seen danger. I felt in tune with the zeitgeist. The position of the antagonist was one I adopted deliberately and which I thought was my rightful role in society.

As I analysed this position more deeply, and in conversation with those who know my work well, I concluded that whilst my impulse was antagonistic, often driven by a sense of anger at the injustice of things, my work carried inside it a world of dream, desire and imagination that did not dictate to my audiences any terms of human engagement but rather proposed a series of landscapes, meanings and possibilities that created an affective space for making a (progressive) future. In the creation of this space, I was compelled by a sense of injustice (as an antagonist) to offer up, if not solutions, then pathways to find them (as a protagonist).

On reflection, I started to question the alchemy of this configuration within my practice.

Why? Because the conditions of the artist were deteriorating along with the conditions of society. It had become clear that the managerialism which had carried neo-liberalism into the hearts and minds of business, labour and civil society had also intoxicated those within the arts and that, as a result, the artist had moved to the bottom of a very long food chain. In terms of her influence, income and agency, the artist was at nil-all. This is a persistent frequency throughout Side 1 Wall of Noise.

In processing this argument and refining it, I came to the view that the 21st C is a time for the artist to, if not forsake the role of antagonist and adopt the role of protagonist then certainly in my own case, re-calibrate the alchemy of their configuration in my practice and behaviour. I have had the most help in framing my thinking around this re-calibration from Belgian political theorist, Chantal Mouffe:

What is needed in the current situation is a widening of the field of artistic intervention, with artists working in a multiplicity of social spaces outside traditional institutions in order to oppose the program of the total social mobilization of capitalism.[146]

I processed the meaning of Mouffe’s provocation through a discursive framework in successive calls-to-arms in several publications, the latest of which, Year Zero, appeared in Dancehouse Diary, Australia’s quarterly essay for dance in 2016.

Artists need to intervene in non-arts environments. We need to see our artistic practice as a dramaturgical tool for civil society. Let’s be bold. We need to develop not only an artistic dramaturgy and a cultural dramaturgy but a progressive, social dramaturgy. We need to operate cross-sectorally and think transversally. We can no longer enjoy the luxury of being the antagonist. We need to drive the narrative, be a protagonist.

Unless artists define themselves by making work without consideration to the criteria of government, unless they seize control of the language in which policy is forged, unless they write the story of culture in which they are leading characters, unless they understand deeply the complicity of their participation in the various contexts in which they work then our labor, our artworks, our role and agency in society will diminish – and economic modes of production will be an end without a means. Working for nothing. Zero.[147]

This re-calibration of the roles of antagonist and protagonist is one I have been undertaking for a decade and publicly prosecuting since 2013. It encapsulates providing solutions, identifying and navigating new pathways, leading advocacy and resistance. It adopts the posture of ‘the front-foot’.

Of course, it is one thing to know that one’s practice is altering, it is another to understand how and where it is doing so; alterations in practice are more palpable than articulate. For myself, they are produced by concomitant changes in domestic, financial, social, cultural and artistic circumstances. One gradually becomes aware of a re-configuring of one’s interests and intentions before one is aware of a move into a new, definite artistic space.

On reflection, I have developed a new way of speaking, framing, motivating and making through a process of trial-and-error, ‘sensing’ my way to understanding what kind of a protagonist I need to be and can be, and how to balance this with my agency as an antagonist. In so doing, I have become more ‘public’ in a way I had not been. As this process is still in train, it is not as defined as that which describes my earlier period of work. I do understand, however, that the interweaving of certain work streams, real-world events and practice experiments have been influential.

In terms of performance research, the international collaboration, AMPERSAND, allowed me to draw together the practices of body listening and the practice of democracy. In terms of public discourse, the thinking and writing that generated the quarterly essay, Re-Valuing The Artist In the New World Order, developed my capacity to actively engage core arguments about the arts and its relationship to civil society by using the language of artistic practice. In terms of advocacy, the events from the 2014 Sydney Biennale to the 2016 Federal Election helped crystallize my agency in explaining the contexts in which the artist works and her complicity within them. These three threads line the entire album, Wall of Noise, Web of Silence.

Mouffe, Chantal. Agonistics: Thinking the World Politically. London Verso 2013: P.87

Year Zero. Dancehouse Diary, Dancehouse. Melbourne. April 2016 (http://www.dancehousediary.com.au/?cat=724)

(6) AMPERS&ND 2011-2014 AMPERS&ND is the most recent research stage of the Body Listening protocols, extracts of which are interpolated throughout Side 2 Web of Silence. AMPERS&ND reinvigorated a trajectory that began in the mid-90s but which tailed off in the latter years of the 2000s.

Historically, Body Listening had been built with a core group of actors and dancers as principal collaborators.[148] AMPERS&ND introduced musicians into the research mix for the first time, and this element created a new reaction in the process, particularly in relation to language.[149] For example, the meanings of ‘sound’ and ‘listening’ were completely renovated. With its ambition to create a new artistic language that could be read and performed in real time, the ensemble trained with the Body Listening protocols over 4 years in 3 countries and this constancy allowed a new dimension to emerge in the sensibility, language and application of the protocols.

During the first research stage at Hellerau Arts Centre, Dresden, in 2011, we refined a persistent, historical line of inquiry into the question: how do we sense what we can neither see nor hear? We became interested in developing a presentation form as an answer to this question using body listening as an inter-media training system. So we worked on refining the language and presentation structure to make it more accessible and readable. As we were dealing with complex ideas and provocations, the trend was to ‘distil, refine and simplify’. We introduced usable descriptions of critical elements such as referring to our proprioceptive faculty as an internal GPS. We concentrated on the live-ness of the ‘atomic exchange’ between the performers, and between the performer and the audience so that the audience could gradually become immersed and complicit in the work. We came to understand that this complicity was key to them investing and losing themselves in the immediate experience, and also whatever applications we might pursue on a practical, artistic plane. [150]

By the time we concluded the main research phases in Dresden, Melbourne and Chuncheon in 2012,

NYID’s body listening (had become) a training and practice protocol that speaks to artists across the performing arts enabling the formation of a highly sensitised, connected ensemble. [151]

Consequent to this formation, we believed we had developed a new way of ‘speaking’ to an audience about how humans define themselves in the ‘space of daily life’ through their body and their senses, using sound as a primary agent of receiving and processing information. In Seoul, we aimed for the audience to sense and feel an ‘atomic’ connection to the performers and to each other, a connectedness at its most basic level: listening to the sound of one’s body in a room with other bodies.[152]

Roiling underneath this practice, and directly informing it, was a shift in Australian politics created by the New Guard, post-Howard. I deliberately shied away from critiquing the Rudd Government as an artist giving it an opportunity to establish itself. At the time, it was a curiosity – the first change of government in 11 years.

I admired Rudd declaring his first day in office Sorry Day and was moved by the speeches and the symbolism of the occasion. It seemed there was a real sense of possibility about the new government. Some months later, I was invited to attend the 2020 Summit in which ‘leaders’ from all streams of society came together to proffer new ideas for government policy.[153] There I was also moved by the speeches and symbolism of the occasion. In 2010 when I was living and working in Brussels I watched transfixed as Rudd was replaced by Australia’s first female Prime Minister. Once again, I was moved by the speeches and symbolism of the occasion. After 3 years, it seemed the only things at the disposal of the incumbent government were political speeches and symbolic occasions. Its next 3 years reduced the speeches to noise and the symbols to silence.

Noise and silence: a binary that distils the essence of the realpolitik of the 21st C. It is also a binary that has a deep resonance in the training protocols of Body Listening. As I watch Australia’s political culture complete its neo-liberal project and, in the process, disengage society from democracy, it occurs to me that Body Listening articulates an innate, corporeal understanding of the impulses that are integral to democracy’s healthy functioning. I describe these impulses in Side 2 Web of Silence as a continuum based on exchange, adjustment, sharing, active listening, and sending and receiving information. I feel that pursuing the Body Listening protocols along these lines might offer an antidote to the infection of neo-liberalism. That information drawn from this spatial-aesthetic paradigm can be used to inform and leverage new models of a democratic civil society, and help navigate democracy’s contemporary challenges.

This inquiry inhabits my curatorial intention for the second edition of 2970° The Boiling Point, a cultural provocation that bears the shape of a festival of ideas and art which I initiated for the City of Gold Coast in 2015. The 2017 edition is themed Practising Democracy [154] and exhibits many of the aesthetic and intellectual connections I have described in this section. The following is a Teaser to the event that will take place in September.

In 2016, Western democracy turned somersaults.

Brexit, Trump, the rise of Le Pen and populist nationalism in Europe.

Rather than fixating on the noise, 2970° goes deep into the quietude by listening to some smart people suggest provocative ideas for how we might make a future we want to live in.

I am experimenting with the degree to which I can insinuate Body Listening protocols and philosophy into the program.

Principal Collaborators in The Body Listening Project include Todd MacDonald, Min Sung Seo, Kim Kwang-Dok, Natalie Cursio, Sara Black, Carlee Mellow and Tim Harvey

Principal Collaborators came from Elision Ensemble and include Richard Haynes, Judith Hamman and Tristram Williams.

AMPERS&ND Narrative 2011-2014, Grant application

NYID Grant Application for the presentation of Atomic @ Seoul International Dance Festival (SIDANCE) October 2013

NYID Grant Acquittal to the Australia Korea Foundation for Atomic @ SIDANCE, 2014

The 2020 Summit (19–20 April, 2008), Canberra, Australia, aimed to “help shape a long term strategy for the nation’s future”

2970° The Boiling Point, Practising Democracy, The Arts Centre Gold Coast, September 7-9, 2017

(7) 2013 Revaluing The Artist in The New World Order If Kevin Rudd’s prime ministership provided the preconditions for activating the idea of Body Listening as an antidote to the denigration of democracy by neo-liberalism, John Howard’s preceding terms created the necessity to develop a new language with which an artist-citizen might adopt the position of ‘protagonist’.

Throughout the late 1990s and early-mid 2000s, Howard skilfully re-made Australia in his own image. He did this by combining a deft use of language with the tactic of ‘wedge politics’ which he turned into a political art form. Howard created un-textured negative space in public debate by breaking the laws of acceptable speech and speech-making so that no one would understand what he said in order that we would all understand what he meant.

It was a new language to maintain power, a language that heralded the beginning of the professional class of politician in a new Australia that was ‘relaxed and comfortable’. This phrase, in itself, was repeated so often that its potency now stems from its repetition, not from its evident truth. It was a seductive mantra that insinuated its values into our view of ourselves. The problem was that the more we were told how relaxed and comfortable we were, the more ill-at-ease we felt. The disconnect, between what we were told and how we felt, was palpable. It created a disabling effect within our social relations and our democratic aspirations, a strategy intrinsic to the neo-liberal political project, the ascendancy of which did not falter with Howard’s political demise so profoundly had he transformed Australian culture and society.

Howard drew inspiration for his re-shaping of Australia from his American counterpart, George W. Bush, and the ‘neo-con’ cabal that stage-managed him. Bush compartmentalised moral values into ‘good’ and ‘bad’, and people into ‘us’ and ‘them’. It was a simple strategy: relentlessly affirm difference until it becomes an inviolable truth. Like a bully in the playground, George W. Bush repeated ad infinitum: ‘You’re either with us or against us.’ Within the space of months, it evolved from a neologism to a self-perpetuating logic, to the point where Australia agreed to participate in a war and kill lots of people in a far-off country. The base logic followed that if we weren’t ‘with America’ then we were ‘against America’. Of itself, reason enough for them to come and kill us in our far-off country.

It’s an approach shared by neo-liberal politicians across Western democracy. Dutch politician Geert Wilders uses it to great effect. Dramaturge Tobias Kokkelmanns explains the tactic as an intention to confuse and disable:

Wilders for instance has often used the catchphrase: ‘This land is not intended to be…’ over and over again. Without clarifying what that intention would be, who intended it, or if there was any intention at all to begin with.[154.1]

This is a clever rhetorical strategy, an art form of modern message-making; its aim is to eradicate complex thinking from public debate. In an effort to deal with the confusion created by the use of politicians’ duplicitous language, the citizen finds herself unable to maintain multiple points of engagement and settles for Bush’s ‘axis of evil’ as an explainer for global relations. This lays the ground for the rise of the populist, nationalist politician such as Hungary’s Victor Orban, France’s Marine Le Pen and, most recently, America’s Donald Trump for whom language is a tool for dissembling.

By the end of Howard’s reign, Australians had lost their mojo in the shadow of illusory fears taken straight from the playbook of George Orwell’s 1984. Our embrace of risk, individuality and independence had been supplanted by the mantra Be Alert, Not Alarmed [155], a recurring meme in Howard’s lexicon. It kept the Australian people in a constant state of enervating arousal, forever on the look-out for undefined threats. The ‘fair dinkum, fair go’ egalitarianism which mythically and empirically defined the Australian ethos slowly evaporated in this climate of anxiety. Our default setting switched from fun to fear: fear of difference, fear of change, fear of shadows. I map out this trajectory in my 2013 Platform Papers, Revaluing The Artist in the New World Order.

My ambition then was to insinuate progressive ideas from artistic practice into the national conversation which Howard’s culture wars had carved into rigid, discursive units. The language of contemporary artistic practice is of necessity a language of progress. Open, inclusive and underscored by a desire for discovering new ways of working, creating and making, it has a dexterity for dealing with change and experiment and which, if introduced into an amplified discursive space, has the potential to expand the quality and depth of civic discourse and action. I demonstrate this in Section 9 of these Liner Notes.

I was also interested in enhancing the agency of the artist in cultural discourse in terms of their authority, voice and significance. History assisted me in this endeavour when a group of artists decided to boycott the 2014 Sydney Biennale.

A Line in the Sand, Interview with David Pledger Theaterschrift, Lucifer #10, 2010.

Be Alert Not Alarmed was an anti-terrorism slogan adopted by the Howard Government in 2002.

(8) Context and Complicity from Sydney Biennale 2014 to Federal Election 2016 On March 7 2014, the Sydney Biennale Chair, Luca Belgiorno-Nettis, resigned in response to an artists’ boycott and protest over the involvement of his company, Transfield Holdings, as a sponsor of the event. Transfield Holdings was a subsidiary of Transfield Services which had recently won the contract to operate the Manus Island detention centre.

The artists’ objections were manifold but can be distilled into a single motivation – to resist the context in which their work was exhibited as it implied their complicity in Transfield’s business activity. Concerned that, through their participation, certain meanings would be attributed to them and their artwork – that the internment of people seeking asylum was morally and ethically agreeable to them – they resisted. In doing so, the artists exposed the often, invisible circles of context and complicity that exist around art making.

These circles brush up against each other, often overlap and, when they do, are crucial to the production of an artwork’s meaning which is found in the complex agency of the aesthetic context in which it is made and the social and political contexts that govern its presentation. Such agency is determined by the artist’s complicity within these contexts.

These circles of action and connection are central to our dramaturgy as artist-citizens, as is our understanding that the meaning of an artwork is not simply in and of itself – its meanings are multiple and multipliable, and wholly dependent on all the conditions of exhibition and presentation.

The many discussions inspired by the Sydney Biennale artists’ actions that coursed through independent and mainstream media, and which were instigated and organised on social media, enabled the arts community to unpack in detail the ethics of complicity in the exhibition of works of art. Out of these discussions grew a purposeful language and ethical intent that was hitherto absent from cultural discourse. For many independent artists, like myself, it helped them articulate their positions during the backlash that was to come.

High-profile protests and boycotts by Australian artists are not commonplace nor are they completely unprecedented – notable actions have been previously directed against the 1973 Mildura Sculpture Biennale and Tasmania’s 2003 Ten Days On The Island. What distinguished the Sydney Biennale Boycott was the political reaction from the incumbent government.

Then Communications Minister Malcolm Turnbull theatrically described the artists’ actions as ‘the sheer, vicious ingratitude of it all’.[166] The Arts Minister, Senator George Brandis wrote a letter to the Australia Council asking it to develop a policy that would deny funding to events or artists that refuse private sponsorship.[167] Both Brandis and Turnbull (now Prime Minister) have been in an adversarial relationship with the arts since their public responses to the Sydney Biennale Boycott which precipitated a series of events that culminated in Brandis’ retraction of Australia Council funding and the establishment of the National Program for Excellence in the Arts, a connection made by myself and other public arts figures.[168]

The resistance that formed around Brandis’ actions led to a concerted and united front of independent artists and small-medium arts organisations around #freethearts which was instrumental in establishing a news-worthy Senate Inquiry in 2015 that helped the sector prosecute its cause nationally.[169] Out of that configuration, ArtsPeak, an unincorporated and hitherto quiet federation of arts organisations, put up its hand to be a national advocacy platform for the arts. In the frame of the 2016 Federal Election, ArtsPeak successfully co-ordinated a National Arts Debate, persuading the newest Arts Minister, Senator Fifield, the shadow Minister for the Arts, Mark Dreyfus and The Greens spokesperson, Adam Bandt, to attend. Mobile and responsive groups of artists formed such as The Protagonists. Congregations around a variety of hashtags – #Ausvotesarts #artmatters #istandwiththearts #dontbreakmyart – and the Art Changes Lives petition appealed not just to artists and arts workers but audiences and citizens as well.[172] The new Arts Party made a political play for votes with Senate candidates receiving a top-6 preference vote from more than 10% of all voters and a preference from more than 1.5 million Australians.[173] For the first time in over 20 years, the arts became an election issue.

During this time, I endeavoured as a commentator to shape industry and public thinking through various journals and publications; as an activist and organiser developing strategy for national sector meetings in Canberra, Sydney and in Melbourne for the National Arts Debate and as an artist in a one-off campaign launch in the middle of the Federal Election in Canberra called David Pledger Is Running For Office. It was a unique, multipolar context in which I found myself entirely complicit.

The #freethearts hashtag was created by Nicole Beyer of Australian Theatre Network and media commentator, Van Badham. It was then adopted sector-wide by an alliance of artists and cultural operators that drove the grassroots campaign contesting Brandis’ actions.

(9) The Last Line 2017 As this concept album makes its final reverberations, I propose that I have articulated a strong case for which the arts may operate as an analytical prism through which observations can be legitimately and positively refracted to broader society. I have attempted to achieve this through a careful and productive use of language, and in so doing, by the carriage of the language of artistic practice into a broader vernacular and social application. I close now with two concrete contributions arising from this decades-long research and application.

Protagonist For the word ‘protagonist’, I prosecuted its use with a very specific end in mind – to encourage artists to see themselves as leading figures in the cultural discourse rather than objects on which the discourse is projected. In Year Zero (2016), I re-framed an argument that I had developed in a previous essay – The Arts is No Place for an Artist – which I had written off the back of a keynote that I had been invited to deliver for the 2014 Festival of Live Art Symposium, Art and Encounter – and to which I have previously referred.

We need to develop not only an artistic dramaturgy & a cultural dramaturgy but a progressive, social dramaturgy. We need to operate cross-sectorally & think transversally. We can no longer enjoy the luxury of being the antagonist. We need to drive the narrative, be a protagonist.

The idea that artists should shift their modus operandi (their dramaturgy, or operating system) and behave in ways that were not consistent with how they had been behaving for a generation struck a chord with a broad cross-section of Australian artists. This was particularly evident in the #freethearts campaign that set itself up in response to Brandis’ incursion on the Australia Council – discussed on Side 1 Wall of Noise – and, even moreso, in the lead-up to the 2016 Federal Election.

Inspired by Year Zero [174] which was re-published on several platforms, a group of young, established artists organised around the name The Protagonists two months before the 2016 Federal Election. A collective of inter-dependent artists and arts workers operating across and between disciplines, The Protagonists initiated and organized one of the major arts campaign events on June 17 – A National Day of Action.[175] Many other artists responded directly to my idea of the artist-citizen as protagonist and sought counsel, advice and mentorship including dancer-choreographer Matt Day, performance-maker Jamie Lewis, artistic director Alison Plevey, interdisciplinary interventionist Rebecca Conroy and the artists of the Canberra-based 2016 national platform, Strange Attractor.[176]

Dramaturgy For the word ‘dramaturgy’ I have greater ambitions. The etymology of ‘dramaturgy’ is slated home to 18th C. German practitioner Gottold Ephraim Lessing and his book Hamburg Dramaturgy. Over time, dramaturgy evolved as both a practice and a concept. In contemporary arts practice, dramaturgy accommodates many positions and embraces many tasks. I like this generalist description as it highlights many of the elements central to contemporary discussions of dramaturgy:

Dramaturgy gives the work or the performance a structure, an understructure as well as a reference to zeitgeist. Dramaturgy is a tool to scrutinize narrative strategies, cross-cultural signs and references, theater and film historic sources, genre, ideological approach representing of gender roles etc. of a narrative-performative work.[177]

Dramaturgy has been effectively expanded from its source context – theatre – to apply to dance and film and new forms of artistic practice. For example, NYID’s founding dramaturg, Peter Eckersall, expanded many of the protocols he collaborated on developing within NYID to the dramaturgy of new media (NMD) as ‘a turn to visuality, intermediality, and dialectical moves in performance that show these expressions embodied and visualised in live performance space and time’.[178] Dramaturgy has also proven to be receptive to an expansion into Eastern cultural contexts. Essentially a Western concept, its malleability particularly in live performance allows it to mirror and refract its origins. These are currently being explored in a new regional configuration called Asian Dramaturgs Network [179] of which I am a member.

In an invited lecture to students of the Victorian College of the Arts in 2001, I publicly introduced the idea of dramaturgy as an operating system, a code that generates an artwork. At the same time, I proposed the idea of dramaturgy as having a cultural as well as an artistic frame. Since then I have pursued this notion a step further pushing the envelope to encompass a progressive social dramaturgy.

In a broader application ‘dramaturgy’ is an adaptive notion that embraces the idea of an operating system whether that be of a production or culture. At its core is the element of change.[180]

Dramaturgy is a very powerful concept. It’s flexible inasmuch as it can be transposed into different meanings depending on the artistic context and it can have meaningful value when applied outside the arts. Why? Because dramaturgy has to do with how a thing works, whether it’s a work of art or the world itself.

In an artistic context, dramaturgy is the process of connecting and matting ideas into practice. Dramaturgy is rarely fixed, necessarily adaptive and due to its reliance on collective, collaborative actions inherently resistant to the concretization and commodification of other practice-related words such as ‘creativity’ and ‘innovation’ which, as argued on Side 1’s 45rpmanagerialism in the arts: Impact on artists, have been voided of their meaning in civic discourse and corrupted in their application to the arts and artistic practice.

Central to the notion of dramaturgy is the idea that an artwork is generated by an operating system driven by random and non-deterministic algorithms that are entered and extracted by human actions. Applying the concept more broadly, dramaturgy can embrace the idea of an operating system of culture or society. Because at its core is the element of change. In fact, dramaturgy is defined by change. Its utility as an operating system is determined by its capacity to be altered in a creative and evolutionary process driven by the algorithms of human behaviour.

In a 2016 essay that analysed sport, art and politics through the prism of entertainment, I ventured the following application of dramaturgy:

It’s only in a highlights package that a spectator can read the dramaturgy of NFL (American football). Its operating system – the playbook – is utterly obscured by the entertainment paraphernalia attached to it.[181]

The notion of a dramaturgy can be extended further. I recently employed it when discussing the potential, degree and kind of change imagined by the introduction of a universal basic income, an exercise I was commissioned to do most recently for the publication, Views of Universal Basic Income. [182]

If one thinks of social dramaturgy, or the operating system of a society, as a flexible, evolving series of interweaving ‘human algorithms’ then entering a new algorithm into the system, such as a universal basic income, requires knowledge of both the system and the new piece of code… Our code needs to have the following elements: the principles of support and social value, a clear economic benefit, flexibility in its accommodation of individual circumstances and the right-to-refuse any job outside the identified profession.

Whilst these elements are essential in supporting the life of an artist, they are just as relevant when considering universal basic income in an amplified social space. In the essay, I propose the idea of undertaking sectoral-based pilot schemes to identify elements in the code that would specifically benefit the idiosyncrasies of a single sector and other elements that might be applied more broadly across society. The essay concludes with a telescopic projection ten years into the future where the results of just such a case study on the effects of a UBI in the arts are publicly announced by the Federal Minister for the Arts, Education and Employment, Senator Adam Bandt, and his coalition partner, Deputy Prime Minister, Tanya Plibersek, standing on the steps of the Sydney Opera House. They declare the results to be so compelling that the UBI is going to be rolled out across all sectors of society.

This kind of ‘future projection’ – in which I mix up the past, the present and the future to propose a new trajectory – is one of my artistic tropes. I’ve used it in all of the artworks and many of the published essays that I’ve transformed into tracks on my concept album. I will close with an example that remains both prescient and progressive in an attempt to answer the question I proposed for myself in my abstract-cum-media release:

In 1983, I had dinner with George Harrison at Kinsella’s in Sydney’s Taylor Square. George spoke to everyone at the table driven by his innate curiosity about human beings. Our conversation turned to the then nuclear crisis which prompted him to offer that, if something went awry, Australia was his preferred destination. Around that time, George purchased land on Hamilton Island and built a home there. Scroll forwards to present-day Australia, two years after Fukushima: the nuclear crisis is as real and forbidding now as it was then and Australia is still a viable escape clause for the rich and powerful should something ‘go wrong’. The past tells us that we have learned nothing. We have tread water. Tadpoles in the pond.

Scroll forwards thirty years from now to 2043. If the artist is living and working under the same conditions, we will have tread water once again. And lost a great opportunity. The 21st C is our time. When what we do, what we make and how we work can have the greatest social benefit. We need to work through the ambient fear created by neo-liberalism, push back against the shadow values of managerialism and constitute ourselves as a sustained contradiction. To do this we must fight for fundamentals – industry representation, professional autonomy and financial security. From such a position, we will be visible, capable and central to the key conversations about the arts in society, and help create a society with the arts at its centre. This is our future, the future we need for ourselves, for our children, for our culture and for our society.

If we have to take direct action to make that happen, so be it. We will be following in the footsteps of nurses, teachers, miners, doctors, all who value their work and all whose work is valued. Until we appreciate the essential value of the artist in the New World Order, no-one else will.

We can no longer stay in the pond. We have to swim in the ocean. If we do, then the world will change for the better. Our capacity to shape and imagine a better future is necessary and real.

World Leaders Summit, Darwin, 2043Prime Minister Jack Khan Shmik pondered the options. He was about to give the opening address to the World Leaders Summit and he wanted to hit the right note, to say something that would shape the proceedings of the next three days. His mind was a tumble–dryer, sorting items that needed more attention than others, all of them rolling around in a contained space. He mentally interrupted the cycle, opened the door and scrutinised the contents. A few things stood out. Colour, structure and form. Unsurprisingly, given his previous occupation as a painter — a highly collectable one as his wife reminded him whenever she tried to dissuade him from seeking another term. How could he do that? He was as much a product of Australia’s incredible success story as he was one of its architects. For thirty years he had watched and participated in the appreciation of the value of the artist, a process which had made his country the model for ‘interconnectivity’, the new mechanism–byword of the twenty–first century.

Artists had inserted themselves into every sticking–place of society, into the in–between spaces of the law, banking, manufacturing, environment, on the edges of everywhere and every thing. Their practices and processes, honed in the studio, the rehearsal room, in the privacy and safety of their minds, had become sought after as massive leaps in technology proposed problems that only an acute artistic sensibility could solve. Time and again, artists had developed better questions for solving difficult problems; time and again they had seen the connections between things when others could only see the ‘things’; time and again artists had saved the world from seemingly imminent disaster by engaging the Artistic Mind, a new model for global progress that had been patented and exported to all corners of the world and had drawn its leaders to this city, one of its most remote. Australia was the Numbskull Nation no longer and today’s opening address would mark an historical moment. He stood up still not knowing how to begin and then his mouth opened of its own volition, speaking the words that had become a mantra for a generation of global citizens: “Long Live the Artist…[183]

https://www.facebook.com/artprotagonists June 11 Facebook Post

In Re-valuing The Artist In The New World Order, P 27

The Dramaturgy of Universal Basic Income in Views of Universal Basic Income, The Green Institute, June 2017

Epilogue, Re-Valuing The Artist In The New World Order, Currency House, August 2013